5000 years ago, Native Americans in what is now the southern US created an extraordinary earthwork: Watson Brake took centuries to build and is the oldest mound complex we know about in North America.

We don’t know what it was called or what it meant to its builders; things that happened 5000 years ago are hard to reconstruct. But we try anyway.

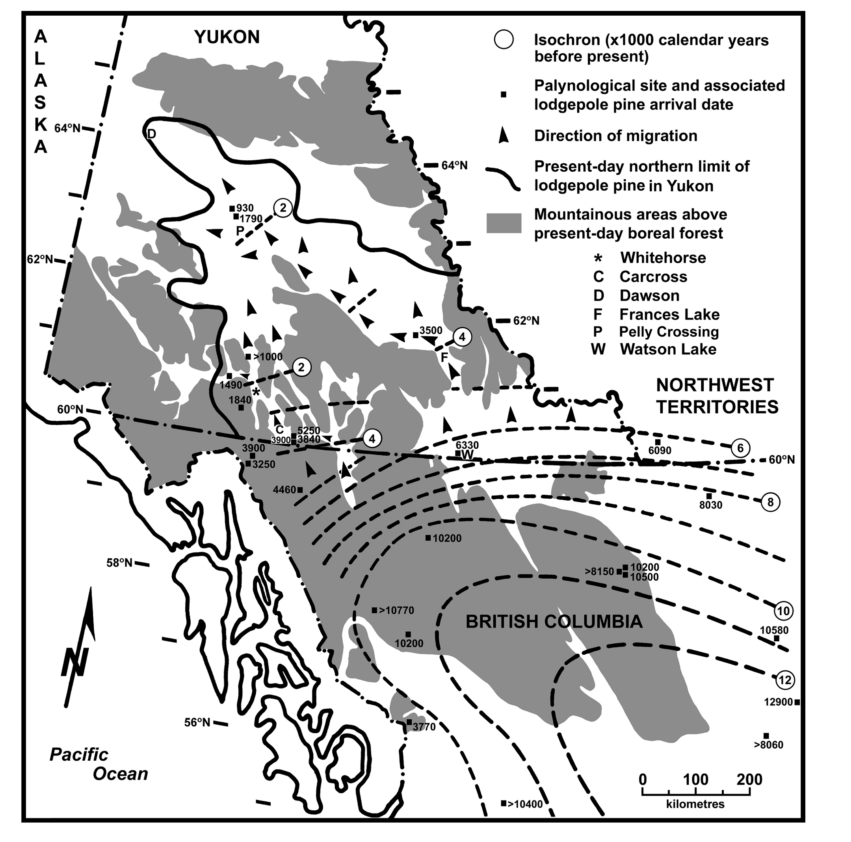

While the creators of Watson Brake were mixing their fish bones into the mounds in Louisiana, the eastern edge of the lodgepole pine migration front was crossing the Yukon Plateau 4000 km away. By the time the last handfuls of soil were being packed onto Watson Brake’s 25 foot tall ridges, lodgepole had hit the high, cold teeth of the Selwyn and Pelly Mountain ranges.

Photo by Ed Struzik of Cirque of the Unclimbables (actually in the Mackenzie Mountains to the east of the Selwyns)

The trees couldn’t cross the high mountains, but they followed the Frances River through a pass just 20 km wide to Frances Lake in southeastern Yukon.

4000 years ago the vizier to Pharaoh Mentuhotep IV led an expedition to Wadi Hammamat where he gave offerings to Min, a fertility god. A few years later, Mentuhotep was dead, childless, and the vizier was Pharaoh. He probably didn’t kill Mentuhotep, but that was 4000 years ago, so who knows?

About the same time Amenemhat was maybe-but-probably-not thinking about usurping the throne of ancient Egypt, lodgepole pushed out of Frances Lake’s narrow valley. Freed from the confines of the high mountains, lodgepole began a slow march up the the Tintina Trench.

The Tintina trench and its extension, the Northern Rocky Mountain Trench, are a longstanding human travel route and geological marvel. I wonder if the trees followed the people or the people followed the trees?

When the first Roman Emperor died, the eastern edge of the lodgepole migration front rounded the top edge of the Pelly Mountains at Pelly Crossing and sprawled across the eastern portions of the Yukon River watershed, down to meet the western migration front slowly making its way through the valleys of the northern Coast Range.

Pelly Crossing. Bridge not available for use by trees.

But lodgepole kept going up the Tintina Trench, too. Today, they’re are all the way up to Dawson. It’s not clear exactly when they got there, but the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in have definitely been there longer than lodgepole has.

People move so much faster than trees that we don’t always notice their incredible journeys. But journey they do!

If you want the details and a discussion of uncertainty around these estimates, check out the paper: Strong, W. L., & Hills, L. V. (2013). Holocene migration of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta var. latifolia) in southern Yukon, Canada. The Holocene, 23(9), 1340–1349. http://doi.org/10.1177/0959683613484614